Colonial Singapore & English Theatre (1840-1945)

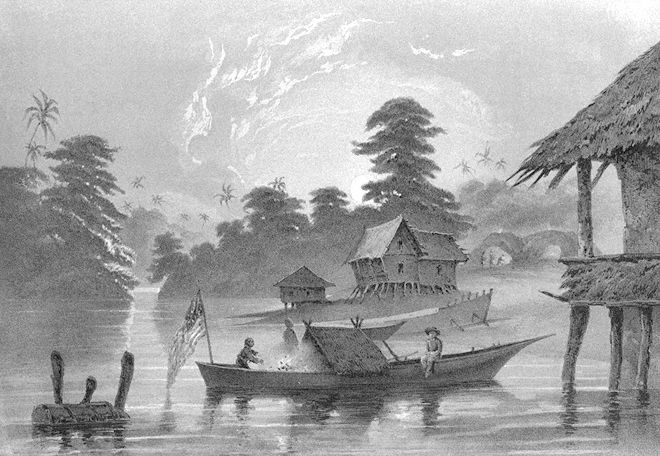

River Jurong, Singapore (c 1856) by Peter Berhard Wilhelm Heine and Eliphalet M Brown.

National Museum of Singapore, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

To begin the story of Shakespeare's arrival in Singapore, one must trace the sea routes and intermediaries through which his plays travelled. Advertisements of the arrival of new books mentioned Shakespeare's plays alongside Josephus's Jewish history, Arabian Nights, and Brigdewater's Treatises in an 1842 column found in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. One of the earliest stagings of Shakespeare in Singapore was advertised in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (18 July, 1844):

MRS DEACLE has the honor to announce, that on Monday the 22nd Inst. will be performing Shakespeare's Play of the MERCHANT OF VENICE, commencing from the 3rd Act, with entire new dresses, decorations, &c. and assisted by the who strength of the Amateur Talent.

Mrs. Deacle, well-known in the Calcutta theatre scene after a long career in India, had travelled to Singapore and stayed between June to late August in 1844, with news about her arrival publicised on 23 May 1844. She prepared a repertory of plays, mostly abridged versions, and Singapore-based amateurs were roped in to perform. She also performed Antony and Cleopatra and took the role of Cleopatra. Like Merchant, Antony and Cleopatra was a selection of scenes of the play that involved only Antony and Cleopatra. Along with these excerpts, she staged the farcical plays The Dead Shot, Valet de Sham, Catching an Heiress, and The Sentinel. Mrs. Deacle's tour signaled the future route that travelling companies and actors would take, making Singapore a pit-stop before travelling eastward to the other English colonies such as Hong Kong and Australia.

Shakespeare at the 'Theatre Royal'

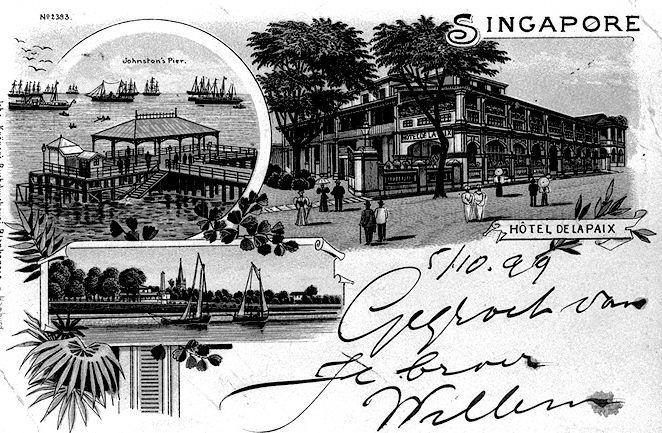

Postcard from Singapore showing (Clockwise from Top Left) Johnston's Pier, Hotel De la Paix, and Elizabeth Walk from the sea, 1899. Reproduced with permission from the National Archives of Singapore. Accession no. 62767

By the 1840s to 1850s, trade routes were well established and British architects were involved in the colonial infrastructure. What was particular about the early theatre spaces in the former colonies was that they were often surrounded by telegraph stations, government buildings, and colonial hotels or were found within the hotels, all within the vicinity.

Names of theatres in the colonies often took the same names of theatres in West End, London. The name "Theatre Royal", for instance, was inscribed all over England, Calcutta, and Singapore. Spaces like this were ‘exclusive playhouses, determined to insulate themselves from the natives, so that even the ushers and doorkeepers were English. (Jyotsna Singh 2003, 102).

This name "Theatre Royal" began to appear in advertisements and reviews of performances since the 1840s. More specifically, Theatre Royal was in fact the dining room of the London Hotel. At that time, there were three hotels in Singapore: the London Hotel on the open promenade lawn or Esplanade overlooking the harbor (now Padang), the Adelphi Hotel on High Street, and the Auckland Hotel at Bonham Street.

The London Hotel belonged to a Belgian named Gaston Dutronquoy, who was also the ticket manager for all performances that were held in his hotel. He used the dining room as a theatre and local amateurs enacted comedies. A few talented gentlemen played the parts of ladies, so well in fact that on at least one occasion one of them was mistakenly chatted up afterwards by a visiting gentleman (Van Wyhe 2013, 71). It was in this "Theatre Royal" where Shakespeare was first performed in Singapore, with cross-dressing and abridged plays the norm.

Singapore Town Hall and Theatre Royal. G. R. Lambert., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Town_Hall,_Singapore_-_1860s.jpg

Theatre Royal Town Hall

(later Victoria Theatre)

In 1860, the town hall building was being built and performances were put up by an amateur group to raise funds to build the theatre at the ground floor of the town hall, which was, as you might have guessed, later known as Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall after the turn of the century. It was at this new venue where Shakespeare became a staple source of entertainment for the European audiences.

In 1862, after a series of delays and resistance from the local church, the Theatre Royal Town Hall was finally built. By the 1890s, however, the stage was actually considered poorly designed because it failed to meet Victorian standards: no scenery or backdrop could be properly placed, the stage was too near to the audience to create the perspectival depth that was required for proscenium stage pictures.

In fact, in 1891, one reviewer commented that:

In Singapore unhappily there is no stage on which scenery can be satisfactorily displayed; and the nearness of the stage to the audience, and its absence of any effect of distance, make it exceedingly difficult for any travelling company to create those illusions which are so essential to the enjoyment of the play [...] The unsuitability of the Singapore Town Hall as a theatre was a subject of universal remark between the acts and after the play (‘Mr. Miln’s Company in “Hamlet”, Straits Times Weekly Issue, 3 March 1891, Page 4).

George Crichton Miln & Alan Wilkie

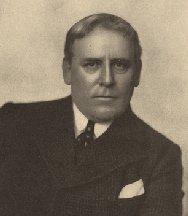

By the 1890s, and with the established sea routes across the Suez Canal in place, British actors and travelling troupes travelled to the British Empire fully versed in the Shakespeare repertoire. Often economically staged, with scenes cut and actors in multiple roles, such troupes brought Shakespeare to the expatriates who had long missed the West End. London-born George Crichton Miln (1851-1917) brought his theatre company on this established route, travelling to the English colonies of India, Singapore, Australia, and eventually, Japan (Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagasaki). He arrived in Singapore in 1891 as a stopover and was received with much anticipation.

His early profession as a Unitarian preacher in New York most likely influenced his performance style. Critics also pointed to Miln’s innovations, and how he utilised theatre technology to captivate his audiences: Miln’s production of Hamlet had several changes which apparently gave ‘novel’ ideas of Shakespearean plays to his Asian and Australian audiences. For example, the farewell admonition of Polonius to his son was omitted altogether, as was the King’s repentant prayer and Hamlet’s diverted purpose. Above all, a sudden flash across the stage in the closet scene as a substitute for the visible entrance of the Ghost was the most striking feature in Miln’s production of Hamlet.

Such innovations were ardently welcomed by the audience. The reviewer of Sydney Morning Herald remarked that Miln’s Hamlet was staged ‘as it has never before been staged in the colonies’. In various newspaper columns of the Straits Settlements, one can observe the mechanism involved in promoting a touring company long before it arrived at a city. For Miln, the Singapore press promoted his tour and reviewed his performances throughout his stay. For instance, a reviewer had this to say about his staging of Hamlet:

It is difficult to describe accurately the qualities of Mr. Geo. C. Miln and the dramatic company who on Wednesday night produced “Hamlet” at the Singapore Town Hall Theatre. It is the misfortune of the dramatic companies on tour that there is a tendency to create highly coloured anticipation; and the position of Mr. Miln as an actor of Shakespeare’s great plays must be judged to some extent by what he claims to be. If his ambition be simply to produce Shakespeare’s plays as they used to be produced by the stock companies of the better theatres in the great provincial towns of England, assisted by one or more “stars” of varying brightness, then Mr. Miln has succeeded in his attempt…Their dresses, their appointments, and their scenery are all good, and the latter if it had a chance to be displayed would no doubt deserve all the encomiums which have been passed upon it by the Indian press. (Straits Times Weekly Issue, 3 March 1891, Page 4)

Miln would go on to stage several plays from his Shakespeare repertoire including Hamlet (25 Feburary 1891), Merchant of Venice (27 Febuary), Romeo and Juliet (28 Febuary), Julius Caesar (3 March) after his trip to Hong Kong was delayed, Othello (5 March), Richard III (7 March), Macbeth (10 March) and on 12 March, he performed Hamlet again as part of his farewell benefit. He was also invited to play cricket with non-commissioned officers of the 58th Regiment at the Recreation Club, where they drunk with enthusiasm to about two in the morning.

George Crichton Miln, Image taken from ERBzine, Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine, available at:

https://www.erbzine.com/dan/m4.html

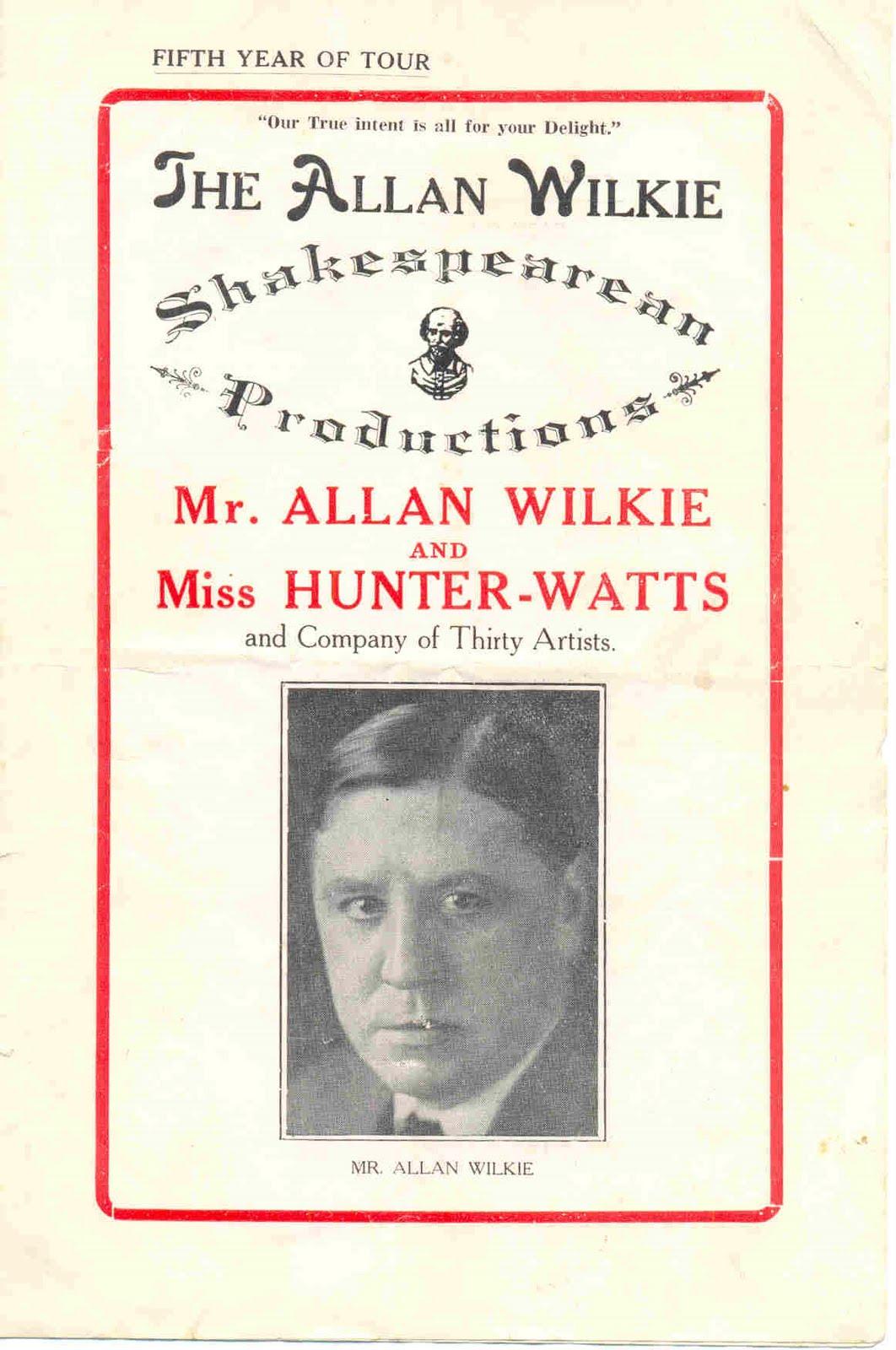

Allan Wilkie, Programme of First Year of Tour. Image taken from History of Australian Theatre (HAT) blog, available at:

http://hat-archive.blogspot.com/2010/10/allan-wilkie.html

Some two decades later, Allan Wilkie, an English Shakespearean actor of Scottish descent, visited Singapore with his London Company between 1912 and 1913. By comparison, Allan Wilkie's version of Shakespeare was not as well-received (and even thought of as “authentic” in Japan) as compared to Miln’s.

Alan Wilkie was staging plays by Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde and British theatre at that time was already going through changes in style and form and subject matter. Miln was a populist, a showman. But Wilkie was more interested in staging modern plays in the British ports of India, Australia and Singapore, though he also staged Shakespeare as colonial cargo.

He arrived in Singapore on 23 August 1912 but it was only during his return trip when he staged As You Like It on 20 February 1913 as a Saturday matinee performance. A reviewer notes how the audience "mainly composed of young folk— but none too numerous— found pleasure" in the performance. That said, "the scantiness of the audience on the occasion of such a delightful piece is somewhat surprising in view of the fact that Shakespeare's writings are so popular among Asiatic and other local students while the opportunities of seeing his works on the stage are very few and far between. (The Straits Times, 24 February 1913, Page 9). Indeed, the reviewer's comments hint at the rarity of Shakespeare being staged in Singapore at the turn of the century.

Sir John Gielgud in Singapore in 1945

It was only in 1945, where the next famous Shakespearean actor travelled to Singapore to perform. "For Some Must Watch," Sir John Gielgud performed his Hamlet over the course of a week (14, 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24 December 1945), though tickets to the shows were only available to the units of the British Army stationed in Singapore. This prompted the local newspaper, The Straits Times (16 December 1945), to appeal to the Ensa Garrison Theatre (what the Victorial Theatre was then called) to release tickets or open a couple of performance for local civilians to watch "Mr. Gielgud's interpretation of 'Hamlet'."

See the cute video below to find out more about Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall:

Victoria Memorial Hall (Garrison Theatre), Singapore, 1945. Reproduced with permission from the National Archives of Singapore. Accession no. 2008-001140-AB